Author Archives: Kara Pemberton

So you’re a professional now – your webcomic has a fan following, you post regularly, and you’ve quit your job to finally pursue your dream of being a webcomics artist!

… Now what?

You’re not syndicated by a newspaper, you don’t get paid a salary to post comics to the Web, how do you make a living on drawing webcomics?

Through selling yourself and your work on every possible medium. Social Media is a very effective outlet for this, if you brand yourself and your comic name, then when you produce content there will be people willing to buy it. And you can produce content other than webcomics, most of the more popular comics will start to sell merchandise: T-shirts, plushies, exclusive content, bags, you name it. Commercializing your comic is a good solution to funding yourself.

But not everyone wants to buy comic merchandise, especially not if your comic isn’t that well-known yet! So what else can you do?

Another common thing comic artists do is Patreon, a website that let’s people subscribe to a comic to get special incentives – such as reading comics early, draft drawings, doodle posts, all sorts of things. Webcomics also often have PayPal donation buttons so readers can directly pay any author they like.

Source: Patreon

Other funding websites include GoFundMe, or more commonly, Kickstarter. Kickstarter is usually used when an artist is trying to fund turning his webcomic into print for the first time – an expensive initial endeavor.

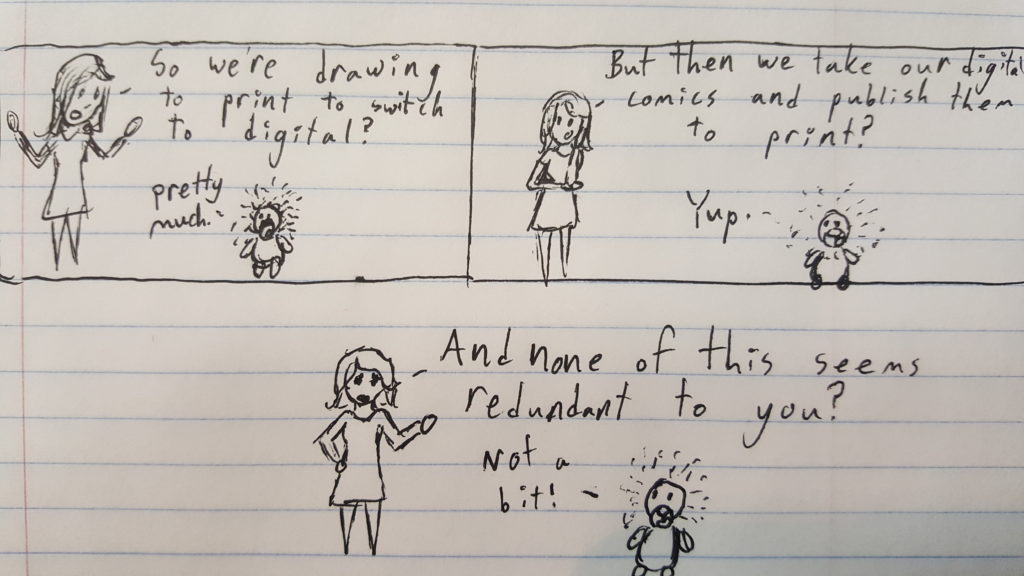

Turning a comic into print is the most common way of funding it. Even though distributing comics through a digital format is wonderful and open and creative, since the Internet is free it’s hard to support yourself through it.

“Social Justice” are two words that are a hallmark of our generation. It has always existed in some form or another; often it was referred to as “civil rights” or “human rights”, but in its current incarnation it’s known as Social Justice. Social Justice generally means everyone’s rights to economic, political and social opportunity. However, it also has the unfortunate connotation of the “Social Justice Warrior” or SJW, which is a condescending way of referring to people who take social justice to the extreme.

Source: Sailor Swayze

However, no matter how much some people look down on it or dismiss it – social justice is seeping into all parts of our digital world. Including webcomics.

Social Justice is one of the many contentious issues on the web, with those fighting for issues of civil rights, and those arguing that modern “social justice” is millenials (our generation) being too sensitive about things. And the internet provides a platform for both of these viewpoints in equal standing. There is a large community of support for people of all identities; LGTBQ, POC, immigrant, differently abled, anyone who has experienced discrimination in any way. And there are some wonderful webcomics and comic producers coming from these communities. Strong Female Protagonist handles a number of rights issues, but from the perspective of superheros (much like some people think the X-Men acts as a metaphor for gay rights). And other webcomics have started as a more typical comic but transitioned into social justice, simultaneously evolving their characters.

But these comics still have their critics, some getting quite angry at the webcomic creator wanting to change their own webcomic. Once again there is the example of Sinfest, a comic that has dramatically changed since its inception.

Source: Sinfest

The dialogue between comics supporting Social Justice and those making of “Social Justice Warriors” is constant and often inflammatory. Both sides tend to be dismissive of the other, and echo the way most YouTube comments devolve into insults without being productive. This is a problem throughout the Internet, as tone and other social cues are non-existent in a digital forum. And unlike in the time of Newspaper comics, webcomics can have a sort of dialogue with each other, and have contrasting viewpoints in a public space and in response to each other.

Source: Shortpacked

No matter what your opinion on Social Justice is, it’s being explored in a way heretofore un-imagined through the digital format.

How do you become a well-known webcomic artist? What is the quick trip to success?

Short answer: There is none. If you want to make a webcomic to become famous you’re in the wrong profession. The main way have a famous webcomic is to be doing it a really long time or get lucky. But beyond that, the best way to become popular is to be good, and there are a few tricks that the pros use:

Write to a Niche Audience; or really write to an audience you relate to. Penny Arcade, and Ctrl+Alt+Delete are some of the most popular video game comics out there. And Piled Higher and Deeper is a well-known comic about graduate students and the struggles they face. These webcomic artists write to a topic they know, and do it well. People in similar situations can relate to the experiences of the characters and therefore enjoy reading it.

Make your characters compelling; There are a billion video game comics out there, what makes comics like Ctrl+Alt+Delete stand out is the storylines of the characters woven in with video game commentary. Other stories create fantastical situations and then insert very human characters into it; such as PvP, and Questionable Content. Questionable Content in particular focuses on the conflicts and emotions people deal with through sad and complicated situations; focusing on topics such as alcoholism, suicide, depression, OCD, and a number of other things. We don’t always like the characters, but we can always empathize with them and what they’re going through.

Have something unusual: Even in the most true-to-life comics, there’s usually at least one character or aspect that is fantasy-like. Girls with Slingshots has Pedro, a talking cactus. Something Positive has Choo-Choo Bear, a seemingly liquid cat. And Dumbing of Age has Amazi-Girl, a student who acts as a superheroine but definitely shouldn’t physically be able to do what she does.

NSFW: Not Safe For Work

This is both a warning to those in the workplace that what they’re reading is not for polite company and a warning to young people that the content is not for them.

It’s also an invention almost exclusively created for the Web. When things were in print parents wouldn’t have to worry as much about their children finding and being able to access a porn magazine, certainly not a whole store’s worth. But now, with few restrictions placed on Internet browsing and what websites can be accessed, there is an inherent danger of kids finding things they’re not supposed to. So when it comes to webcomics, how do you screen something like that?

Well in many ways, you can’t. At least not the PG-13 things. Many webcomics will self-identify the age group they’re appealing to, but that information isn’t always readily available on the site – usually it’s only shown through a hosting site that lists webcomics. And some of the R-rated websites will have no screening process either.

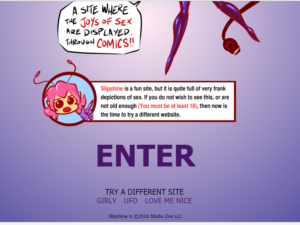

However, as a common courtesy rule of thumb, most webcomics rated R, especially ones that are pornographic in nature, will have a screening page.

Source: Slipshine

It may not technically block people from accessing the site, but it let’s them know what they’re getting into. These sites will usually warn “NSFW” or “17+”, and if a parent knows how to screen Web access these will be words that alert any screening system.

No one can protect their children from everything on the Web, but those who produce content for the Web should help them try.

You’re 7 years old. Your mom has gotten you one of those super cool “choose-your-own-adventure” books. You flip back and forth through the pages, going through every possible scenario and timeline, and you can’t help but wish there was an easier way to do it.

So yes, now we have games – but what if we wanted something more open-ended? What if we wanted something almost like a conversation, a story developing through suggestions and development from multiple people.

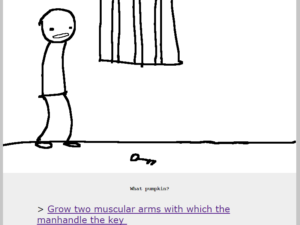

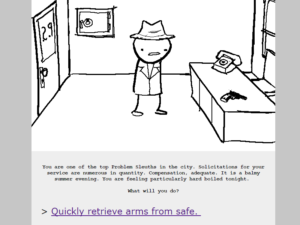

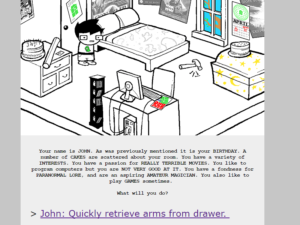

One of the most well-known webcomics on the internet is Homestuck, a webcomic by Andrew Hussie on the host website of MSPaint Adventures, about a group of teenagers playing a simulation computer game that causes catastrophic real-world events. It is a massively complex comic now, but it started as a choose-your-own-adventure style comic, very similar to the text-based game of Zork. Zork was an interactive fiction computer game, best known for the quote “it is pitch black. You are likely to be eaten by a grue.” It’s never fully explained what a grue is, but it nonetheless compels you to act in a certain way (light a match, nobody wants to get eaten!) Interactive Fiction comics act in much the same way, by providing set options or refusing certain commands. The author is still the ultimate controller of the story. However, this doesn’t prevent readers from having fun with the author or the author poking fun back, as with the continual joke of Andrew Hussie not drawing his characters with arms.

Source: Jailbreak

Source: Problem Sleuth

Source: Homestuck

This interaction between audience and author is even closer for interactive fiction than it is for the normal webcomic. While every author is likely to receive audience story suggestions, few follow them – or even respond. In a traditional story writing format, it’d be rude to throw your suggestions at someone and expect them to take it. It’s like writing to J.K. Rowling and saying “yes I know you’ve already finished the story and that’s great, but I really wanted Draco and Harry to be in a gay relationship, can you change your existing canon to accommodate my fanfiction?” (yes I know Dumbledore is now gay). But with interactive fiction this response is practically invited. It’s like having a planning meeting for a TV show, where you may be the director/writer but you’re listening to others suggestions and responses and accepting the ones you like.

While there are interactive comics hosted on their own page like MSPaintAdventures, most are located on Tumblr or other forums. These are much easier for hosting, because of the forums’ quick response time and audience input, and the function of Tumblr’s question box for audience suggestions. Tumblr in particular has an entire community of ask blogs, usually based on existing franchises but with OCs (Original Characters) or unusual takes on existing characters ‘running’ the blog and answering questions. This puts whole new meaning to fans having control or influence over the storyline, because these fans have created their own canon and their own interactive universe.

Why isn’t interactive fiction more of a thing?

What is a hiatus?

According to Google, a hiatus is “a pause or gap in a sequence, series, or process”.

According to webcomic readers, it’s the most frustrating thing to happen to your favorite comic. And potentially the most terrifying. Because to many artists/writers, making webcomics isn’t a “job”, and it’s easy for “real life” to get in the way. If you’re not syndicated or receiving some sort of payment for your work, the rest of your life ends up taking priority. This is also where fillers come into play.

But public hiatuses bear an element of dread, because there’s always the possibility of a comic being abandoned. Breaks can become permanent, and authors can go missing, pulled into the dredgery of mundane jobs. It’s a difficult thing to consistently run a webcomic, so it’s important to be understanding of artists that are just unable to keep up with it – as much as it might pain fans of the series.

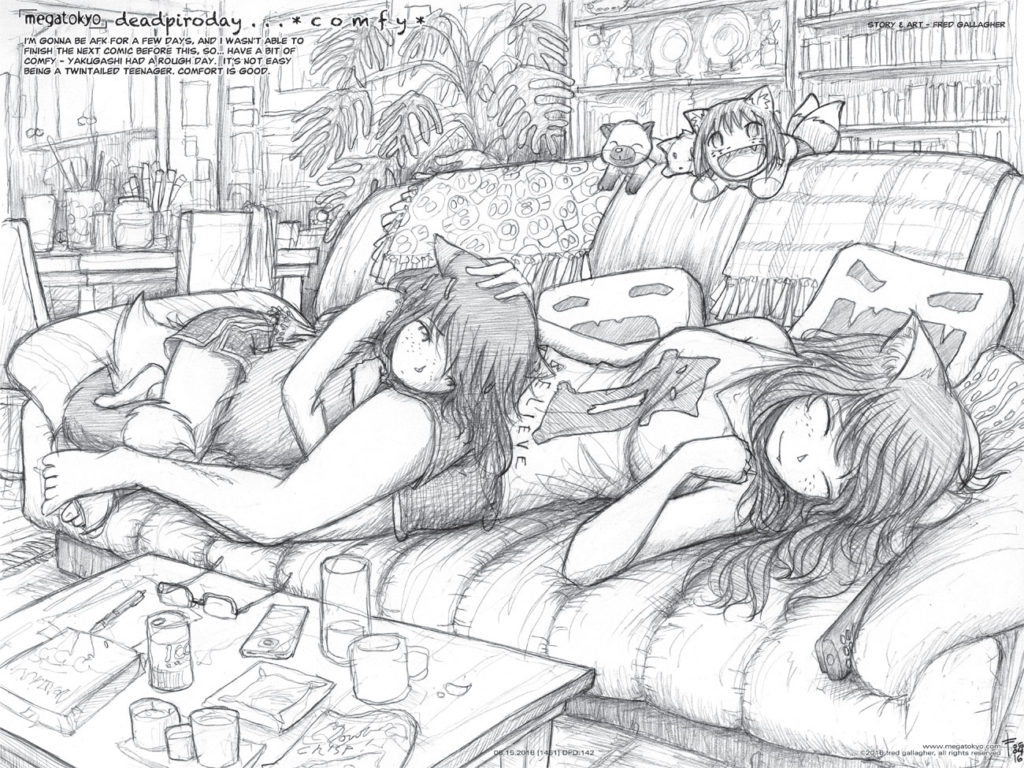

While there are a number of series to go on hiatus at some point in time (occasionally due to important life events like getting married or having kids), there are some series whose hiatuses are as prevalent as their updates. A prime example of this is MegaTokyo – renowned as much for its anime-like characters and dramatic storylines as for its almost constantly being on hiatus.

Source: MegaTokyo

Though these breaks are often because of personal trauma or tough experiences in the author’s life, they occur so frequently as to become a trope that the comic itself is known for (in addition to its overload of other story tropes).

All of this is why most webcomic creators create a strip buffer for themselves, or a stockpile of previously drawn comics that can be used within the series in case the author ever gets behind or gets busy. This is also an important part of maintaining a consistent posting schedule, because no matter how hard you try some days will not be drawing days. So if you ever want to create your own webcomic, give yourself a buffer. Don’t be on never-ending hiatus.

All comics have themes.

In order to have a successful comic you need to have a theme. It creates boundaries that you have to work within, which in turn allows you to be more creative and compelling. Garfield is about a fat cat and his owner, with other animal characters that communicate through thought bubbles. Calvin and Hobbes is about a young boy and his imaginary friend/stuffed animal Hobbes and their adventures together. Beetle Bailey is about a lazy soldier in the army and his strict and easily angered sergeant. When you break them down, these are all rather unusual story ideas to start with. Not everyone is going to be able to relate to being in the army, or owning a cat. But within these narrow themes, larger ideas and thoughts can be communicated. Calvin and Hobbes is known for being a startlingly insightful comic, and every reader can relate to the innocence and wonder shown in the comic. The characters in these comics echo sentiments we ourselves feel or can relate to in some way.

Some comics do this with a more direct approach, such as For Better or For Worse and Zits.

Source: For Better or For Worse

Source: Zits

These two newspaper comics have both taken the approach of drawing/writing about family life, with all of its trials and tribulations. However, they took two very different approaches.

For Better or For Worse has characters that have grown throughout the years. It started in 1979 and had a family with babies, and then had those babies grow up and have kids of their own. After 29 years of continuous strips, the author retired from the daily production of strips. But because of how popular the comic strip and its characters were, all of the comics are being republished, through the newspaper format. There are a few minor changes or new strips, but for the most part fans are getting the opportunity to grow up with the characters all over again.

Zits on the other hand has a theme based on a high school teenager living with his parents. Because the theme is specifically about teenagers, the characters in the strip don’t age. The look of the comic sometimes does, and the content changes a bit to accommodate changes in the world (smartphones and other technology, as well as fad changes) or to advance the characters (his friend Hector growing facial hair, him dating Sara, etc.). But the content and theme of the strip don’t change, and so the comics remain fairly consistent and easy to pick up on any given day.

Webcomics function much the same way. They have a set theme that they start out with, whether that’s corrupted versions of care bears, evil scientists, superheroes, or college. But the major difference for webcomics is that most start with a specific story in mind for that theme. There’s a lot of variation within that, but because of the nature of webcomics, many authors are taking advantage of the format to create graphic novels online.

Source: Girl Genius

In this format, updates are published in the form of one page of a comic, rather than a self-contained joke. This can be both excellent and frustrating, as it is dependent on a consistent readerbase and regular updates. But it’s a very effective form of creating a graphic novel, because it establishes a fanbase before your comic is even published.

Ultimately, themes are the box within which you build your comic. Sometimes they expand beyond where you ever expected them to go, and others exactly follow the original plan of the theme and storyline. It’s impossible to predict where your story will take you.

If you open up a newspaper to find the funnies, there’s probably a few things you’re expecting.

- A specific group of characters per comic

- A consistent art style

- A consistency in content

Part of being a newspaper artist is having a comic that is completely consistent, that doesn’t change styles or content, so readers know what to expect and don’t have to keep up with it every week. They can just open up any newspaper and enjoy whatever content is there.

Webcomics function a little differently. While they can exist as a series of stand-alone comics, most take advantage of the existence of archives on the web to catalog their stories, develop their characters and change their art style. Bill Holbrook, author of Kevin and Kell, says that the reason he created Kevin and Kell as a webcomic (and currently the longest-running one), was to take advantage of the existence of archives to build longer narratives and more complicated storylines. Kevin and Kell also exists as a newspaper comic, but its primary publishing is through the web.

Source: Kevin and Kell

However, as with any aspect of the web, archives carry their cons as well as their pros. Many webcomic artists have changed their artistic style over time, or improved in artistic ability. And it can be painful to know that anytime someone new finds your comic, they immediately go to the “horror” that is your first art. And sometimes this will turn people off from the comic if they’re not a fan of the original art style. But it also means that the artist gets to experiment with their art style, and try new things over the series of the comic.

Say you don’t think your old content is professional enough. Or you want to redo it/publish it in a more professional fashion. Many webcomic artists will turn their comics into a series of graphic novels. It’s created a reverse from the old standard of regular comics being converted for the web. And it provides a unique challenge to artists, because many don’t start their comic with the possibility of printing in mind. So it’s a long process to go back through and re-format things, or re-organize daily/weekly content to be viewed all at once.

The archive also can be a dangerous pit to fall into for those artists whose style has changed over the years. It can be a very tempting thought to go back and redo your old comics to match your updated style and advanced art ability. But then your artistic ability advances even more and your style changes, and you have to redo them again. And again. And again. And pretty soon you’re never writing new content, just redoing the old over and over again.

The creation of social media meant that our past would never truly be private again. And the existence of archives means our artistic past never will either. But both show how much improvement can be made over time, and humanize the author of such content. We are all evolving, learning people, who make mistakes and go through terrible periods and learn from it. The comic Sinfest exists as an epitome of this. The author begins with fairly good art, and somewhat biased, inappropriate comics or jokes, that clearly show his worldview and sense of humor. But as the comic goes on, his art style begins to change, and with it his content. He goes from making jokes about a potential “matriarchy”, to creating a feminist resistance group within the comics that fights the patriarchy. A patriarchy that exists in a fashion similar to the matrix in coding people’s behavior and assumptions. His characters go through drastic reformation of thought and personality, and through the lens of his comic we see his own worldview changing. And it’s not something that could have been predicted or planned for, and it’s not something that could have happened in newspaper comics. It exists solely because of the nature of the webcomic.

Source: Sinfest