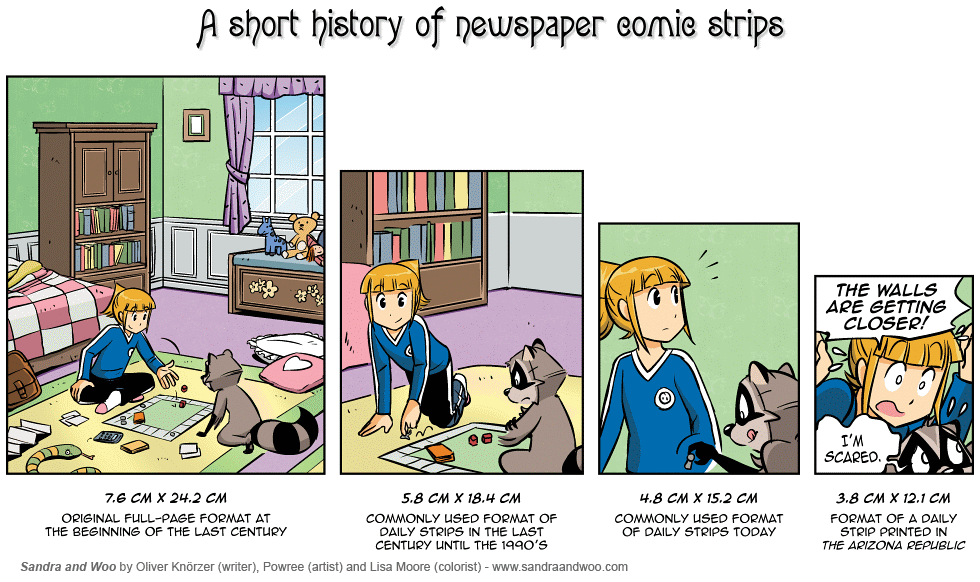

The size of comics being published over the years has always followed a standard format. Whether it’s full pages of comic issues on an 8 1/2″ by 11″ page, or the newspaper comic strip . . .

Source: Sandra and Woo

. . . Comics have always had a standard size and format to follow. At least, until they moved to the web.

Scott McCloud, author of “Understanding Comics”, is generally considered a pioneer in the realm of comic scholarship. He created one of the first official studies of how comics operate, why they appeal to us, and what they could mean in the future. And he did it all in comic form, employing the format in a way it had rarely been used before. After the success of his initial book, he wrote two sequels – Making Comics, and Reinventing Comics. In both books he delves further into the comic creation and the comic industry, including the possibilities of webcomics. He even has his own webcomic, which recreates his famous comic Zot! in a wholly unique format. As someone who wants to push the edge of comic storytelling, he has created his own take on using the web to expand the storyworld both visually and conceptually. In this page you see Zot and Jenny falling, and you have to scroll and scroll as it recreates the feeling of characters falling. A similar approach is used in the blog post popularized on Tumblr, “Do you love the color of the sky?“. One of the most impressive examples using the scrolling comic is To Be Continued, which shows new panels and events only as you scroll to them. McCloud takes advantage of this not only by having one continuous panel, but by having interlocking storylines with panels offset from each other and lines connecting each panel to the next. It’s similar to a mapping interface, and creates a form of cohesion and clear process of panels/events while immersing the reader into the comic.

Scrolling comics aren’t the only ones who challenge our traditional understanding of comic space. Xkcd is known for having a deceptively simple style of stick figures that the author uses to delve into complicated topics, or to highlight unexpectedly detailed drawings. A prime example of this is xkcd’s comic about how big the world is; which upon first glance looks like a normal comic. The only clue that you can explore the digital space is the title of the comic, Click and Drag. When you do this to the final panel you see all the space that exists “beyond” the square containing the comic. The artist has created a huge “world” that you can explore until you get tired of clicking and dragging – because it’s still only possible to see the drawing through the small square provided. This is an excellent tool for creating the illusion of more space, and for controlling where the reader looks without them realizing it. Another example of this is Hobo Lobo of Hamelin, which is also a scrolling comic but also reveals more of the world as you slide your computer screen to the left. It provides a clear direction for the reader and rewards them by creating the illusion of movement and revealing more of the story and characters.

There is an infinite amount of potential space on the web. As creators we’re all doing our best to fill it in the most unique ways possible.